en-counter-maps

In the en-counter-maps project we looked at the relationships between art and archaeology through several different media. We found a common theme that was related to examining maps and their representations, and through the map we mediated our critical relationship on the processes of making and doing art and archaeology.

In total we devised 4 pieces. The pieces were called Inferstructures, Maps of places called Bolungarvík, Threads, and A 1913 Map of 2011 Bolungarvík.

The map is in many ways a simplification of the landscape. The multiplicity of landscape is reduced to one dimension of its visual qualities – the god‘s eye view from above – which is a highly subjective, disembodied representation. The intention with Infer-structures was to extend this trajectory of god‘s eye mapping to one of its consequences by reducing the map to one of its dimensions – the road system. Furthermore we wanted to attempt to represent the experience of place when travelling through it by car, which is a representation we considered quite relevant to Bolungarvík as there is such a clearly defined road system through it. The piece effectively focuses on one line – the road – while every other lines and trajectories fade into the background. This is the experience of a town as a ’path of least involvement’, where the only definable elements are its escape routes. The painting is naturally placed by the side of a road. We chose to use archaeological trowels to sculpt the blue background, while painting the lines with a brush. This creates a tension in the painting. We as archaeologists thought it might be appropriate to see the chaotic background as representing the material affordances of the landscape – its archaeology – and the lines as its histories. The lines are simple, clear, structured, but if they are not maintained and reiterated they quickly dissolve into the background.

We chose to use archaeological trowels to sculpt the blue background, while painting the lines with a brush. This creates a tension in the painting. We as archaeologists thought it might be appropriate to see the chaotic background as representing the material affordances of the landscape – its archaeology – and the lines as its histories. The lines are simple, clear, structured, but if they are not maintained and reiterated they quickly dissolve into the background.

The painting later fell down into the grass, and we felt that this fit well with its wayward message.

The painting later fell down into the grass, and we felt that this fit well with its wayward message.

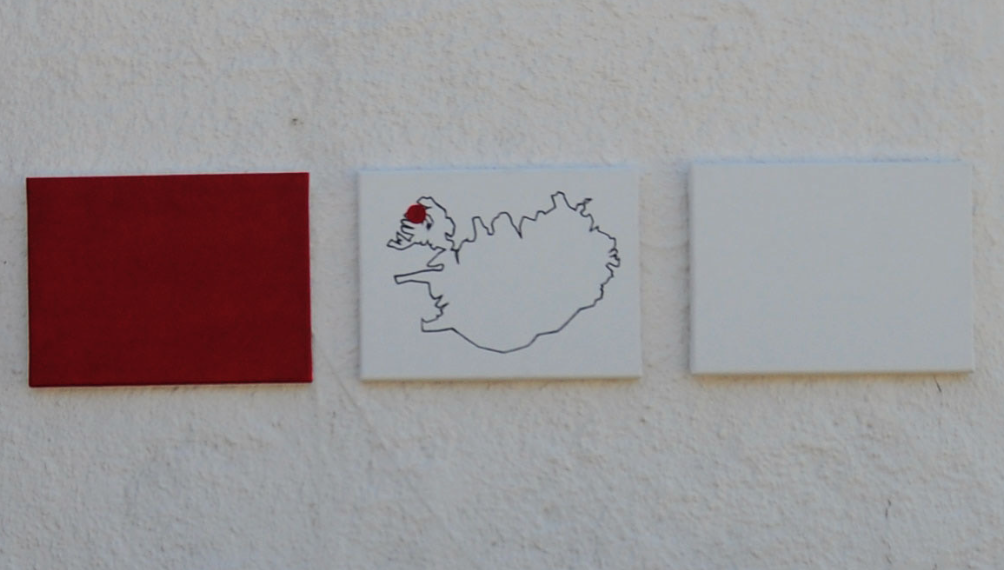

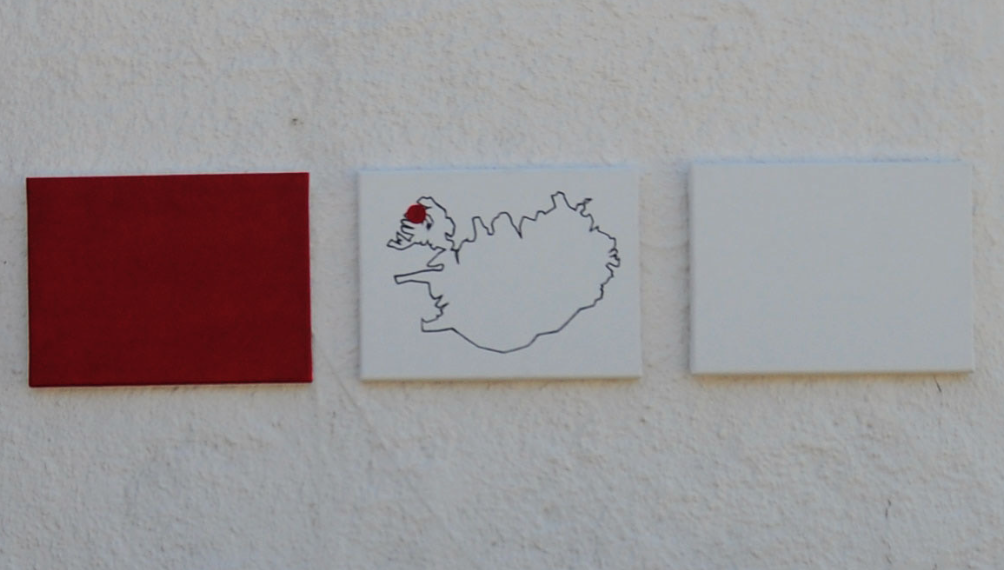

Robert Smithson once wrote that “you cannot visit Gondwanaland, but you can visit a map of it.” This remark was the starting point for Maps of places called Bolungarvík. Iceland as a place only exists on a map and its existence is entirely based on the scale which is used in making the map. That is, experiencing Iceland in its wellknown cartographic form requires the map (unless one is able to travel to outer space). All three paintings are simple representations of places called Bolungarvík, but so far we’ve only discovered one place by this name. The red painting is at the scale ∞:1, the white painting is at the scale 1:∞.

Robert Smithson once wrote that “you cannot visit Gondwanaland, but you can visit a map of it.” This remark was the starting point for Maps of places called Bolungarvík. Iceland as a place only exists on a map and its existence is entirely based on the scale which is used in making the map. That is, experiencing Iceland in its wellknown cartographic form requires the map (unless one is able to travel to outer space). All three paintings are simple representations of places called Bolungarvík, but so far we’ve only discovered one place by this name. The red painting is at the scale ∞:1, the white painting is at the scale 1:∞.

Iceland in its cartographic form exists on a thin strip of scale somewhere in the middle.

This work proved to be similarly mobile.

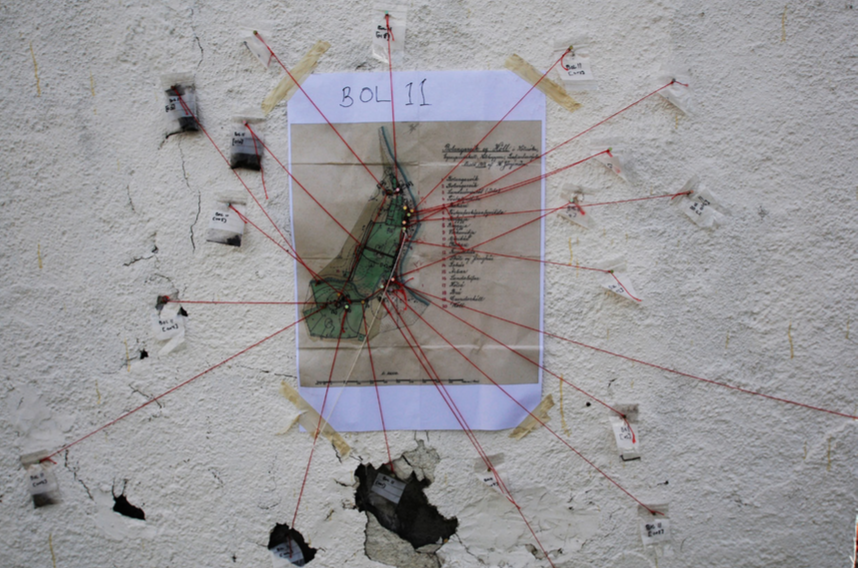

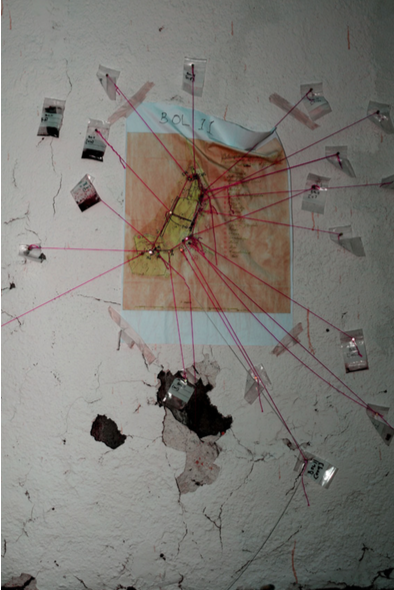

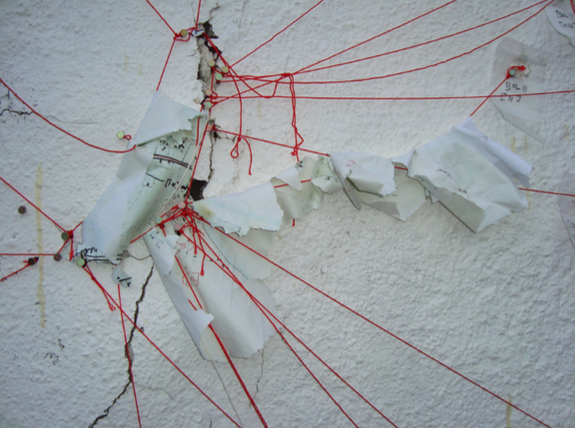

Threads mediates the underlying tensions in our collective pieces. In this interstitial position it connects the representational pieces (Infer-structures and Maps of places called Bolungavík) with the fourth (1913 Map of 2011 Bolungarvík). As it moves back and forth being pulled but also pulling the threads that connect them, this mediation is in constant process – in a state of becoming. Personal histories, stories about places, the rational scientific gaze and authoritative histories all intersect that set in motion new translations.

Threads mediates the underlying tensions in our collective pieces. In this interstitial position it connects the representational pieces (Infer-structures and Maps of places called Bolungavík) with the fourth (1913 Map of 2011 Bolungarvík). As it moves back and forth being pulled but also pulling the threads that connect them, this mediation is in constant process – in a state of becoming. Personal histories, stories about places, the rational scientific gaze and authoritative histories all intersect that set in motion new translations.

A 1913 Map of 2011 Bolungarvík was a piece in four parts – the construction/installation of the site/lab, a performance of the archaeological process of excavation, and the interpretation and production of archaeological artefacts and bodies of knowledge after the excavation had been completed. The last part occured on the day after the excavation when we performed the ‘closing’ of the site, by incavating into the trenches many of the objects we had found and used during the process. However, a further part became apparent as we closed the trenches, as the pale grass emphasised the location of this 'happening'. Furthermore, the trenches were still visible long after the performance had ended. The incavated objects continue to change under the surface, and may perhaps one day be excavated by a group of bored archaeologists, curious artists or perhaps a mixture of both.

A 1913 Map of 2011 Bolungarvík was a piece in four parts – the construction/installation of the site/lab, a performance of the archaeological process of excavation, and the interpretation and production of archaeological artefacts and bodies of knowledge after the excavation had been completed. The last part occured on the day after the excavation when we performed the ‘closing’ of the site, by incavating into the trenches many of the objects we had found and used during the process. However, a further part became apparent as we closed the trenches, as the pale grass emphasised the location of this 'happening'. Furthermore, the trenches were still visible long after the performance had ended. The incavated objects continue to change under the surface, and may perhaps one day be excavated by a group of bored archaeologists, curious artists or perhaps a mixture of both.

Central to this piece were two maps: 1913 and present-day. The residual features in the present-day map of the 1913 map provided the archaeological spatial dimension for our performed interventions: the trench locations, the act of digging, creating an archive of the excavation, and the then the incavation and closing of the site. The process resulted in a radical transformation of the area infront of the exhibition house – and partially extended into the exhibition space - From an area of land, to the site of an excavation, to its textured interpretation on the surface – as land art – and finally back again to an area of land. Through the archaeological process as a performance we draw attention to our practice and the spectral absence that we bring presence to and what we have put back into the land through our spatial and temporal transformations.

Central to this piece were two maps: 1913 and present-day. The residual features in the present-day map of the 1913 map provided the archaeological spatial dimension for our performed interventions: the trench locations, the act of digging, creating an archive of the excavation, and the then the incavation and closing of the site. The process resulted in a radical transformation of the area infront of the exhibition house – and partially extended into the exhibition space - From an area of land, to the site of an excavation, to its textured interpretation on the surface – as land art – and finally back again to an area of land. Through the archaeological process as a performance we draw attention to our practice and the spectral absence that we bring presence to and what we have put back into the land through our spatial and temporal transformations.

A 1913 map of 2011 Bolungarvík reflects on the critical relationship that the other pieces the pieces were suggesting about the relationship between representation and the nature of intervention, whether artistic or archaeological. In fact, what we hoped to achieve was a performance that was both neither of these things - simply a process of doing something - but at the same time could be called both art and archaeology. In the both respects we were quite successful. The process orientation was used to examine the trope of repetitive action and performance, and the representation/intervention examination achieved a conversation or dialogue between art and archaeology by blurring the boundaries between them and creating something that was unique

A 1913 map of 2011 Bolungarvík reflects on the critical relationship that the other pieces the pieces were suggesting about the relationship between representation and the nature of intervention, whether artistic or archaeological. In fact, what we hoped to achieve was a performance that was both neither of these things - simply a process of doing something - but at the same time could be called both art and archaeology. In the both respects we were quite successful. The process orientation was used to examine the trope of repetitive action and performance, and the representation/intervention examination achieved a conversation or dialogue between art and archaeology by blurring the boundaries between them and creating something that was unique

On the opening day of Æringur

One month later

Two months later

We were delighted that we could display all of our pieces outside the gallery, both on the outer walls of the house as well as on the lawn next to it, since it gave us the opportunity to further reflect on the archaeological nature of our pieces. Left exposed, the taphonomic degradation of the pieces – both the visible and those we had incavated – became an integral part of en-counter-maps. As the house used for Æringur 2011 was an abandoned and condemned house, we also wanted to point out the irony between an old house that was being torn down and the excavation and decay of archaeology/art by showing how the impression of objects are not limited to the surface but is also much deeper, below the skin of the object, in its history and personal connections or threads.

The pieces continue to be transformed by taphonomic processes. During a recent visit we discovered that many of the objects we had used during the excavation had become mobile, exploring the territories outside the excavation area.