Assemblage Theory: Recording the Archaeological Record: First Response

Introduction

This is a response to Andrew Reinhard’s Assemblage Theory: Recording the Archaeological Record. Reinhard’s piece is a playful exploration of what it means to make a "sonic assemblage," and what that assemblage can do. Reinhard collected a variety of freely available sound samples online, assigned himself a time limit, and built an album’s worth of songs from the pieces he gathered. Reinhard’s result is an attempt at a kind of musique concrète, a montage of sounds.1 Reinhard’s piece seeks to create an album analagous to an archaeological context, where “artifacts could mingle together, ultimately settling near each other, providing an odd puzzle of artifacts to try to disentangle.” 4

How I Approached This Piece

I agreed to respond to this without knowing what it was going to be, but intrigued nonetheless. I thought for a while about how I wanted to approach something like this. I decided I wanted to hear the album, then read the narrative explaining choices, and then listen again. The plan was that coming at it a bit cold would allow me to make connections without being unconsciously swayed by any sort of explanation.

But, I knew that I was listening to an assemblage, sounds made from other sounds. I framed my listening as an archaeologist, attempting to understand an assemblage spatiotemporally. These are the types of questions I considered before experiencing the album:

- What can I learn about the creator?

- How can I identify the assemblage’s component parts?

- How do the sounds interact to make a song?

- What kinds of interventions or modifications were made by the creator to fit them together?

- How do the songs, understood as archaeological contexts, relate to one another?

Modern Intrusions and Disturbed Contexts

Reinhard’s shares his album on the Spotify platform, a subscription-based music sharing service. My initial listen resulted in some interpretive challenges. Without a paid membership to the service, the Spotify mobile app randomly shuffles album tracks. Contextual disturbance. Spotify also inserts algorithmically selected songs not on the album. Intrusions. In this case, they seemed to be mass-market dance music. I subsequently learned that the web app will play tracks in order, but the complications introduced by Spotify’s shuffles and insertions did seem to reflect often inconvenient archaeological realities. As archaeologists, we often find contexts in a different arrangement than the order in which they were deposited.

The tracks for Daft Valentine are provided for download. One of my first attempts at understanding the assemblage through these “artifacts” was to identify the source. I want to understand networks of exchange and connections between data sources contributing to the formation of this sonic assemblage. I attempted to use several automated identification tools such as Shazam (https://www.shazam.com/), but these are designed to identify complete songs.

I made an effort to search for the filenames of the provided individual tracks, with no success. This may indicate that the tracks themselves have been renamed or are themselves derivative objects. They are recordings of recordings, or pieces of some original whole. Vessel fragments. Other sounds seem to be created specifically as building components for use in another song. Designed for reuse. Sonic bricks and nails.

Networks of Exchange and Dispersal

While I wasn’t able to find the source of the samples with any of the audio fingerprinting search engines available, I did find something interesting by feeding the Google sound search service the individual tracks: the service identified other songs using the same samples. These all appear to be self-produced electronic, hip hop, and rap songs. Analyzing the “Daft Vox” track returned “Daft Valentine” by Cyphernaut, so, in that sense functionality was verified:

How Sway https://play.google.com/music/preview/T3n3wmhoiyiyj6m6nzfyn7aatda?u=0#

MÃ¥ Jeg by Galsiap Studio, a Norwegian Rap group https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JcmhPhBAFAU

Mellow//Soul by Void https://www.amazon.co.uk/Mellow-Soul-Voidproducedit/dp/B06XD6162L

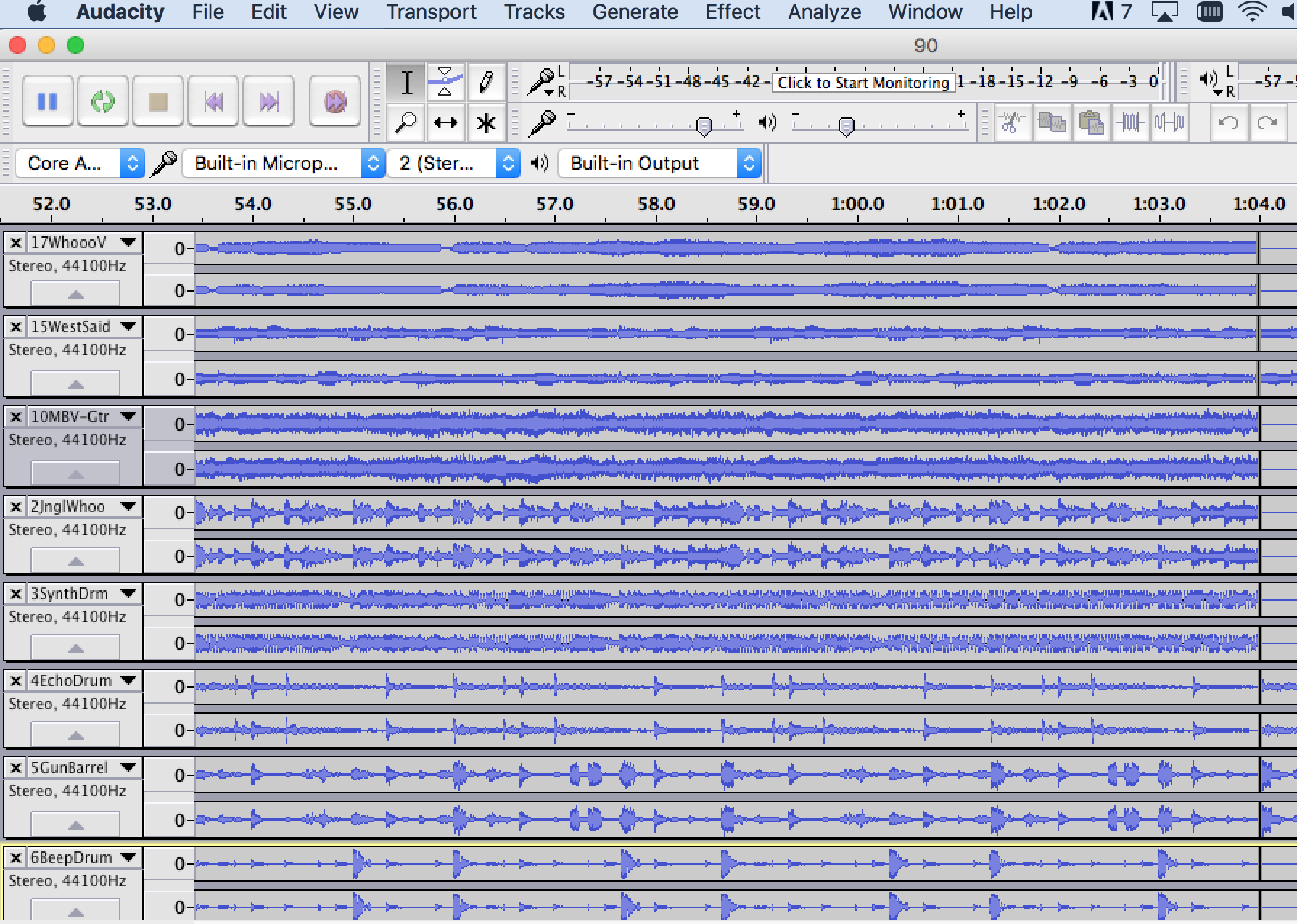

Re-Assemblage

I’ve taken Reinhard’s provided “Daft Valentine” tracks and begun to remix them in Audacity, according to his instructions. My aesthetic instinct ist to stretch, bend, and distort the sounds. It’s a lot of fun, although I haven’t yet produced anything I’d like to share. But the act of chopping up these bits, modifying them and then mashing them (or gently blending them) back together is gratifying and visceral. I’ve also been thinking of what I might do to collect sounds from an actual, physical archaeological assemblage of artifacts.

Sonic Assemblages Elsewhere

When I first learned of Reinhard’s concept, prior to reading his narrative or listening to the album, I thought of two examples of other artists’ work with different types of sonic assemblages.

In David Byrne’s Playing the Building, a series of installations, the artist connected pneumatic mechanisms, percussive parts, and all manner of sound-producing actions from the body of a pipe organ to the pieces of a huge early 20th century building. 2,5

Visitors to the installation were invited to “play the building,” to engage with its materiality and its new sonic qualities. Adults tended to “play” as one would play a piano, attempting to create sense with chords and harmony. Children, however, would just play. The keys on the organ body weren’t actually connected to specific tones, so there was no right or wrong way to play the building. Dissonance and harmony both needed to be explored.

Drew Daniel and M.C. Schmidt, performing as Matmos for 25 years, came immediately to mind when I thought about the sonic assemblage concept. Each of their albums is unified by some theme, and sounds generally come from objects. Their most recent album, Plastic Anniversary, celebrates their musical history and their marriage, while offering a jab at traditional anniversary gift schedules 3. The sounds on the album are all made by plastic: trash, police riot gear, a giant pill. Their songs are sometimes dissonant, others melodic, and often amusing.

These artists begin with the physical, which is an approach fundamentally different from Reinhard’s, but all three experiment with combining, recombining to make a whole that is something entirely different from the sum of its parts.

Final Thoughts

Each track, then, is a bricolage. A cache perhaps? A talisman? A hoard? The assemblage(s) embody the behaviors of collection, curation, modification, and creation. Formation processes remain opaque and disentangling them is out of reach. I came away craving to understand the sources of the sounds. In order to think about this piece like I’d think about an archaeological assemblage, I need to be able to understand the artifacts and their formation, their histories.

Since I’m unable to understand the component parts of the assemblage, I’m unsure that the piece necessarily does what it sets out to do: create a new whole and allow for it to be understandable for an archaeological lense. Nevertheless, Reinhard’s work here stimulated a lot of thought, experimentation, and engagement with sonic materials, and that was a very good time.

Endnotes

1: Anon 2019 Musique concrète. Wikipedia. April 16.

2: Davidson, Justin 2008 My Building Has Every Convenience. NYMag.com.

3: Joyce, Colin, and Noisey Staff 2019 Matmos’ New Album Considers the Beauty and Terror of Plastics. Noisey. March 22. https://noisey.vice.com/en_us/article/43zebn/matmos-plastic-anniversary-interview, accessed April 6, 2019.

4: Reinhard, Andrew Assemblage Theory: Recording the Archaeological Record. Epoiesen. https://epoiesen.library.carleton.ca/2019/02/01/assemblagetheory/, accessed April 6, 2019.

5: Roundhouse 2009 Playing the Building: An installation by David Byrne.

Cover Image "Image taken from page 514 of Œuvres complètes de Lord Byron, traduites de l'anglais par MM. A.-P. et E.-D. S." British Library

Masthead Image Reinhard, Assemblage Theory, Figure 1.